Drones, which until just recently have been associated with either military applications or hobbyist pursuits, have become serious players in the commercial delivery space.

The rapid ascendency of drones was brought into focus when, in late 2019, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) granted approval to United Parcel Service (UPS) to use drones to deliver packages on medical campuses across the United States.

While the FAA’s certification limits the drones’ use to medical campuses (for now), it establishes an important framework for their use and provides a glimpse into the future of aerial freight delivery.

Coverage of the FAA’s decision to approve the UPS drones focused on their speed and cost benefits, both of which are important for parcel services and medical institutions; the latter often require lifesaving drugs (or even organs) on short notice. However, drones offer several other benefits when used for parcel delivery, including a substantial reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in some cases.

If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it

In 2018, RSG assembled a team to study the potential carbon emissions reduction benefits of using drones as part of our freight research and analytics work. The research sought to compare delivery via drone with two other procurement methods: at-home delivery via a service (e.g., Uber Eats) or a personal trip to the store.

At the time, scant research existed on the topic. The research that did exist indicated that any emissions or efficiency gains associated with drone delivery depended on hub locations and vehicle type (when compared to delivery services or going to the store). In other words, individual results may vary.

The existing research also indicated that consolidating deliveries yields energy savings and emissions benefits.

Further, it is known that flight is substantially more energy intensive than ground travel since it requires more energy to keep a vehicle aloft than to roll it along the ground. That said, drones can often travel “as the crow flies,” which is not possible for ground transportation that follows the existing network of roads and highways.

To compare emissions across the three modes (delivery, pickup, and drone), we prepared several case studies that used real-world locations.

These case studies routed vehicles between homes and stores or the drone depot. This process involved siting residential/retail locations and the drone depot on a map. It also required plotting drone and vehicle routes and determining the emissions of each trip.

In all case studies, the drone depot was centrally located among residential locations and commercial/retail destinations. All drones in the case studies could travel approximately 10 kilometers (or 6.2 miles).

For the drive-to-the-store scenario, we imagined an instance where a person needed an item within 30 to 60 minutes. We then estimated the emissions associated with a drive to the closest store and the return trip home.

The RSG team used the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) MOtor Vehicle Emission Simulator (MOVES) model to calculate these emissions. MOVES uses the road classification hierarchy and posted speeds to arrive at an estimate of associated emissions.

For the delivery scenario, we considered two additional scenarios. In one scenario, the delivery driver would already be at the destination and would start there before proceeding to the residential delivery address.

In the other delivery scenario, the delivery driver would start at a distant peripheral location, which includes added emissions since the driver would first need to proceed from their current location to the commercial destination.

The last scenario was the most straightforward in that it routed a drone from the centrally located depot to the residential delivery location. We calculated the emissions for the drones using local data associated with electricity generation and the provider’s own data regarding the power requirements of its drones.

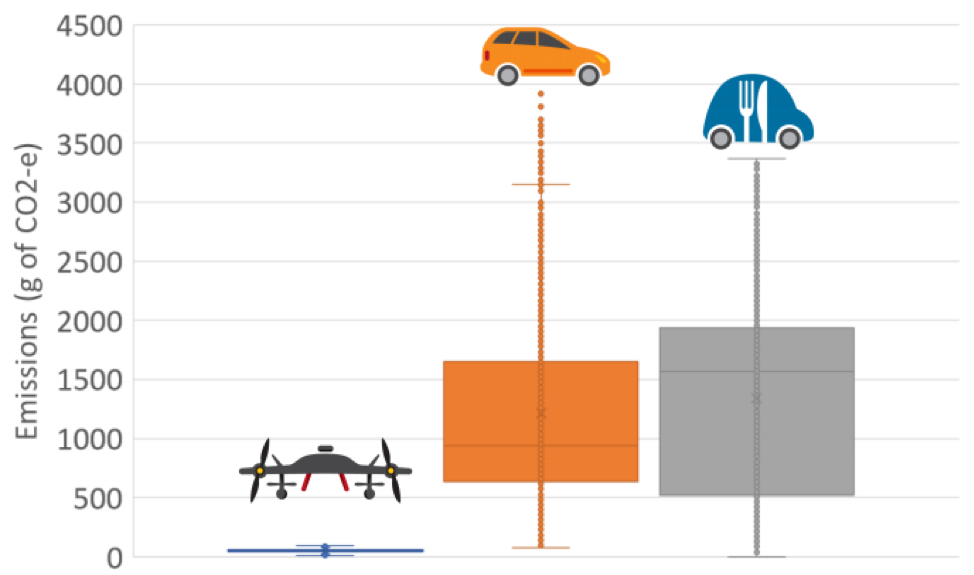

Across all case studies, the results clearly demonstrated the energy efficiency supremacy of drone delivery (as shown in the figure below). This was partly attributable to the fact that the provider’s drone was approximately 10 times more efficient than other drones on the market at the time.

Source: RSG

And while the drones were traveling farther (on average) than the delivery modes in the other scenarios, this increase in travel distance was offset by their small size and light weight. In fact, pickup and delivery generated approximately 26 to 28 times more emissions than drone delivery, respectively.

The delivery scenario had the largest range in terms of its CO2 emissions. This mode produced lower emissions when the delivery driver was already at the commercial location; however, it produced more emissions when the driver had to first travel to the commercial location before proceeding to the residential location.

What these findings mean for the buzz surrounding drones

Our methodology and findings were innovative and demonstrated the impact of drones relative to personal shopping trips or on-demand delivery services.

Overall, drones are incredibly efficient. The design of the drones themselves also yielded significant CO2 emissions savings; in other words, not all drones are created equal.

Further, the number of drone depots, and their locations relative to retail and commercial destinations, will affect total emissions, meaning efficiency will either decrease or increase depending on several factors. The source of electricity generation will also affect total emissions since cleaner sources of power generation will lead to lower emissions overall.

That said, across all the case study locations examined by the RSG team, the relationship between findings remained constant even though the absolute values changed.

These findings are incredibly important for the transportation sector, which, according to the EPA, is now the largest source of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions in the United States.

Companies that ship goods to consumers could use drones to lessen the carbon footprint of their operations. That said, drones are not a panacea for climate change since their load capacity is often significantly lower than existing shipping modes.

However, strategic application of drones in densely populated areas has the potential to chip away at vehicle miles traveled, which is one small but important step toward reducing total greenhouse gas emissions.