Development of a national-level, disaggregated, behavioral-based, and multimodal freight demand model recently concluded with the completion of the third phase of a first-of-its-kind exploratory research study funded by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Exploratory Advanced Research (EAR) Program.

Starting in 2014, RSG has led this work through each phase of research and development. The first two phases designed and built the national freight model. The third phase, which is now complete, calibrated and validated the model for a base year. The working model delivered to FHWA incorporates the national highway network and trip assignments calibrated and validated to the most recent national Commodity Flow Survey (CFS) data from the US Census Bureau.

FHWA is now working with Volpe Center to test the model framework’s capabilities and ready it for continued development and application. Future uses of the national freight model inspire important and timely questions. These include whether its advanced forecasting capabilities can help practitioners understand (or better plan for) supply chain issues.

The national freight model’s disaggregate structure can help practitioners answer more complex supply chain policy questions

Traditional four-step models—freight or otherwise—do not model behaviors. These models do not, for instance, reflect the decisions of individual players, whether they are buyers or shippers. This limits the capabilities and accuracy of these models when developing forecasts.

More advanced models, often called disaggregate models, can model decisions of individual agents within the modeled network. This means users of disaggregate models can answer more complex policy questions. With freight, these questions have usually pertained to long-term growth in demand or sourcing.

More recently, the pandemic has introduced many short-term issues with supply chains, such as bottlenecks at some ports, that have proven more difficult to resolve. However, from a forecasting perspective, the question always comes back to long-term impacts. As supply chain issues persist, there is a growing consensus that the supply chain will not simply snap back to its prepandemic state.

In fact, Yossi Sheffi, who directs the MIT Center for Transportation and Logistics, has said the pandemic has revealed existing supply chain weak points and sped up changes already underway. These changes have included a desire to diversify sourcing and obtain greater visibility into supplier networks.

From that perspective, the national freight model considers these accelerated changes as it would consider other long-term changes. These changes may include less offshoring and the construction of additional factories, such as those that build semiconductors, in the United States.

States could develop a statewide version of the national freight model to better understand freight movements

Both MAP-21 and the FAST Act included several provisions to improve the condition and performance of the national freight network and support investment in freight projects. However, Congress enacted these transportation authorization bills before the pandemic and current concerns over the supply chain. The recently enacted Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act contains billions of dollars to improve roadways, railways, and bridges. If states receive funds through this new law, they may consider a tool like the national freight model to better forecast freight movements.

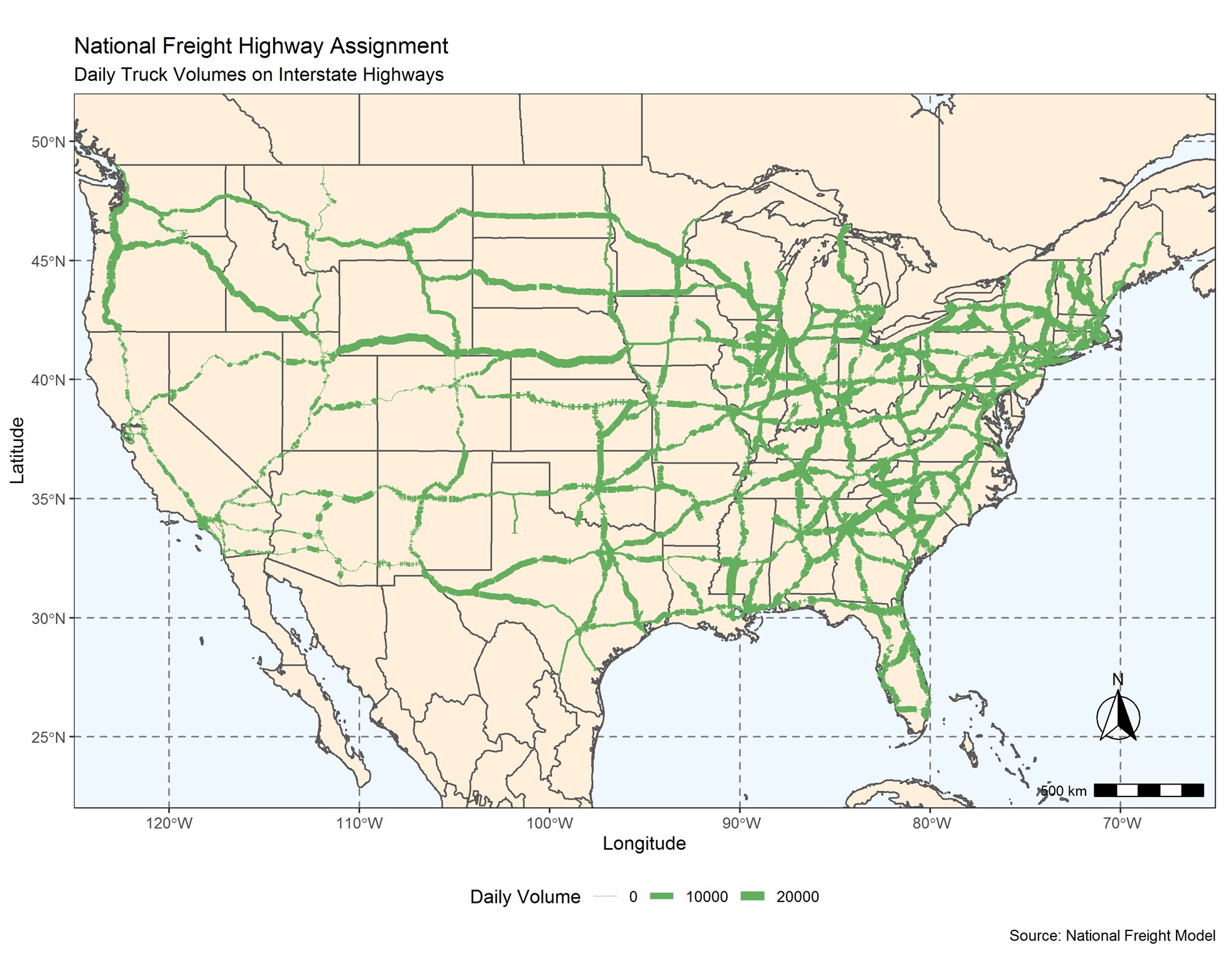

This map visualizes the final output of the recently completed national freight model, which quantifies daily truck volumes on the US roadway network. Line width indicates the level of demand.

The value of a state developing its own behavioral-based statewide freight model is clear. Freight movements into and out of the state could be based on the national freight model’s supply chain network. Most models at the state level currently use fixed tables; however, these are limited as they only allow practitioners to import Freight Analysis Framework data. If states could import data on freight movements directly from the national freight model, then they could consider changes in the supply chain as these occur.

The national freight model cannot untangle supply chain bottlenecks, but it does offer a powerful long-term planning tool for users

Bottlenecks as most people think of them are operational constraints. The national freight model does not include any of the operational constraint parameters that would allow users to answer some of these immediate pandemic-related questions. The only way the national freight model represents operational changes is through travel times. What the national freight model can do, however, is help practitioners understand long-term changes in import and export patterns due to the pandemic.

The focus on improving supply chain efficiency and resiliency is one long-term trend. The national freight model could allow users to see what halving the number of imports from China would mean, for example. But there are model limitations around imports and exports. The national freight model's ports are not capacity constrained; there is not, for instance, a port choice model included.

Users could choose to double demand from all countries west of the United States, creating a similar outcome. However, this then becomes an exercise in scenario planning. This would necessitate additional assumptions on the part of the user. That said, the national freight model would reflect any additional costs incurred by sourcing commodities domestically. The model's forecast and resulting mode choice shift would reflect this.

Increasingly, companies are concerned with longer-term, global impacts—and how those may play out and affect their bottom line. Businesses could use the national freight model to understand wait times and evaluate mode choices for shipping. This could be done by increasing the cost of transfers at ports and terminals in the model. The model output would include a range of options to consider. This is advantageous for businesses because the next few decades may necessitate a longer-term outlook based on multiple scenarios.

Freight modeling helps promote the continued stability and resiliency of the national transportation network

The national freight model represents the successful execution of a significant multiyear research and development project led by RSG. Now in testing, the national freight model will transform how freight forecasts are developed for years to come. Its completion also comes at a pivotal time for the global supply chain and freight movements in general.

RSG’s freight modeling services help agencies develop solutions to freight movement challenges. The national freight model is one example of a tool we have developed to help clients better understand freight movements. One of the best applications of this model is at the state level; this could be achieved by applying truck trip tables directly or by adapting the national freight model to a focused state level.

The national freight model’s utility could be further enhanced through building one or more future years and sensitivity testing. The creation of one or more future years would benefit model users at both the national and state levels who could then access these trip tables. Future sensitivity testing would allow for additional exploration of supply chain issues (e.g., testing with restricted capacity at certain ports).